Historical Origins of Neuropsychology

Neuropsychology's task is to account for how the nervous system produces human behavior.

Modern neuropsychologists originate from all branches of neuroscience. More members of the Society of Neuroscience received training in Neuropsychology (inc. biopsychology and physiological psychology) than any other single field. Modern neuropsychology is relatively new as a distinct discipline. What are the historical origins of this enterprise?

Hippocrates (400 BC): Greek physician of antiquity who is traditionally regarded as the father of medicine. His name has long been associated with the so-called Hippocratic Oath--certainly not written by him--which in modified form is still often required to be taken by medical students on graduating. Hippocrates believed that the brain was organ of intellect, that it controlled the senses and movement. He also noted that lesions produced a contralateral effect.

Aristotle (350 BC): Greek philosopher, pupil of Plato at Athens and tutor to Alexander the Great, Aristotle studied the entire world of living things. He laid what can be identified as the foundations of comparative anatomy and embryology, and his views influenced scientific thinking for the next 2,000 years. Aristotle conjectured that mind and body were merely two aspects of the same entity, the mind being merely one of the body's functions. Localized the "soul" as residing in the heart.

Herophilus (300 BC): Alexandrian physician who was an early performer of public dissections on human cadavers during the single, brief period in Greek medical history when the ban on human dissection was lifted. He is often called the father of anatomy. Noted the difference between sensory and motor nerves but thought that the nerves were hollow tubes containing fluid and that air entered the lungs and heart and was carried through the body in the arteries. Argued that the brain, not the heart, was the organ of intellect; that the third ventricle responsible for cognition, and the fourth ventricle was the seat of the soul.

Galen of Pergamum (150 AD): Greek physician who founded experimental physiology and was one of the most distinguished physicians of antiquity. Galen's influence on medical theory and practice was dominant in Europe throughout the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance. Influenced medical thought for 1000 years. Galen recognized that the arteries contain blood and not merely air. He showed how the heart sets the blood in motion in an ebb and flow fashion, but he had no idea that the blood circulates. Dissection of the human body was at that time illegal (although his early years were spent as a surgeon at the gladiatorial arena, which gave him the opportunity to observe details of human anatomy), so that he was forced to base his knowledge upon the examination of animals, particularly apes. He concluded it was not the ventricles but the brain itself which was important. Attributed the frontal lobes with being the seat of the soul.

Andreas Vesalius (1550): Renaissance Flemish physician who revolutionized the study of biology and the practice of medicine by his careful description of the anatomy of the human body. His methods, which included the dissection of human cadavers, soon convinced him that Galenic anatomy had not been based on the dissection of the human body, which had been strictly forbidden by the Roman religion. Galenic anatomy, he maintained, was an application to the human form of conclusions drawn from the dissections of animals, mostly dogs, monkeys, or pigs.

Rene Descartes (1596-1650): Replaced the Platonic idea of a tripartite soul with that of a unitary mind (res cogitans) distinct from the body. Descartes considered the body and the soul to be ontologically separate but interacting entities, each with its own particular attributes. Believed the ventricles controlled body via hollow tubes (nerves). An early locationist gesture was Descarte's localizing the seat of mind/brain interaction in a particular neurological structure, the pineal gland (chosen because it was an anatomically unitary structure – unlike the rest of the brain -- like the mind itself). Descartes proposed a mechanism [see figure] for automatic reactions to external events. External motions affect the peripheral ends of the nerve fibrils, which in turn displace the central ends. As the central ends are displaced, the pattern of interfibrillar space is rearranged and the flow of animal spirits is thereby directed into the appropriate nerves. It was Descartes' articulation of this mechanism for automatic, differentiated reaction that led to his generally being credited with the founding of reflex theory.

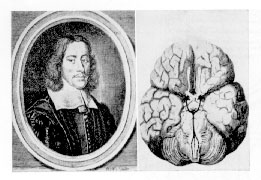

Thomas Willis (1664): British physician who attempted to explain the workings of the body from current knowledge of chemical interactions; he is known for his careful studies of the nervous system and of various diseases. His (1664) "Anatomy of the Brain, with a Description of the Nerves and Their Function"), the most complete and accurate account of the nervous system to that time, he rendered the first description of the hexagonal continuity of arteries (the circle of Willis) located at the base of the brain and ensuring that organ a maximum blood supply, and of the 11th cranial nerve, or spinal accessory nerve, responsible for motor stimulation of major neck muscles. Willis also was first to describe myasthenia gravis (1671), a chronic muscular fatigue marked by progressive paralysis.

Luigi Galvani (1750): Italian physician and physicist who investigated the nature and effects of what he conceived to be electricity in animal tissue. His discoveries led to the invention of the voltaic pile, a kind of battery that makes possible a constant source of current electricity. Found that electrical stimulation of nerve caused muscle to contract. Electrical nature of nerve action.

Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828): Austrian anatomist and physiologist, a pioneer in ascribing cerebral functions to various areas of the brain (localization). He originated phrenology, the attempt to divine individual intellect and personality from an examination of skull shape. Convinced that mental functions are localized in specific regions of the brain and that human behavior is dependent upon these functions, Gall assumed that the surface of the skull faithfully reflects the relative development of the various regions of the brain. His popular lectures in Vienna on "cranioscopy" (called phrenology by his followers) offended religious leaders, were condemned in 1802 by the Austrian government as contrary to religion, and were banned. Three years later he was forced to leave the country. His concept of localized functions in the brain was proved correct when the French surgeon Paul Broca demonstrated the existence of a speech centre in the brain (1861). It was also shown, however, that, since skull thickness varies, the surface of the skull does not reflect the topography of the brain, invalidating the basic premise of phrenology. Gall was the first to identify the gray matter of the brain with active tissue (neurons) and the white matter with conducting tissue (ganglia).

Phrenology: Johann Kaspar Spurzheim (1776-1832) and George Combe (1788-1858). Phrenology enjoyed great popular appeal well into the 20th century but was wholly discredited by scientific research.

The five principles upon which phrenology was based were: (1) the brain is the organ of the mind; (2) human mental powers can be analyzed into a definite number of independent faculties; (3) these faculties are innate, and each has its seat in a definite region of the surface of the brain; (4) the size of each such region is the measure of the degree to which the faculty seated in it forms a constituent element in the character of the individual; (5) the correspondence between the outer surface of the skull and the contour of the brain-surface beneath is sufficiently close to enable the observer to recognize the relative sizes of these several organs by the examination of the outer surface of the head.

Johannes Peter Müller (1825): German physiologist and comparative anatomist, one of the great natural philosophers of the 19th century. His major work was Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen für Vorlesungen, 2 vol. (1834-40; Elements of Physiology). His most important achievement, however, was the discovery that each of the sense organs responds to different kinds of stimuli in its own particular way or, as Müller wrote, with its own specific energy. The phenomena of the external world are perceived, therefore, only by the changes they produce in sensory systems. His findings had an impact even on the theory of knowledge. He was one of the first to advocate the use of experimental techniques in physiology.

Marie-Jean-Pierre Flourens (1825): French physiologist who was the first to demonstrate the general functions of the major portions of the vertebrate brain. Flourens conducted a series of experiments (1814-22) to determine physiological changes in pigeons after removal of certain portions of their brains. He found that removal of the cerebral hemispheres, at the front of the brain, destroys will, judgment, and all the senses of perception; that removal of the cerebellum, at the base of the brain, destroys the animal's muscular coordination and its sense of equilibrium; and that removal of the medulla oblongata, at the back of the brain, results in death. These experiments led him to conclude that the cerebral hemispheres are responsible for higher psychic and intellectual abilities, that the cerebellum regulates all movements, and that the medulla controls vital functions, especially respiration. Flourens was also the first to recognize the role of the semicircular canals of the inner ear in maintaining body equilibrium and coordination. Flourens is generally credited with being the father of experimental brain research. He measured both behavior and brain events. He contended, in opposition to the prior claims of phrenology, that behaviors were not localized in the cortex, and argued, as Carl Lashley later would, that behaviors were diffusely localized, and that lesions led to general losses (Lashley’s law of mass action). He additionally noted that if the lesions were not too severe, that recovery of function was possible, and that restitution of function was the result of compensation by the remaining intact brain (Lashley’s law of equipotentiality).

Camillio Golgi (1843-1926): Italian neurohistologist and neuropathologist. Developer of a staining method (image to right) which allowed individual nerve cells to be visualized. Received Nobel Prize in 1906 (with Cajal) for his work on the structure of the nervous system. Erroneously believed that neurons were not separated by synapses, but were interconnected by continuous neural material.

Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894): German physiologist and physicist, one of the greatest scientists of the 19th century, Helmholtz made fundamental contributions to physiology, optics, electrodynamics, mathematics, and meteorology, but he is best known for his statement of the law of the conservation of energy. Was a student of Johannes Muller. Helmholtz found that the nerve impulse was perfectly measurable and had the remarkably slow speed of some 90 feet (27 meters) per second. (This measurement was obtained by Helmholtz's invention of the myograph). The slowness of the nerve impulse was a blow against vitalism, and further supported those who insisted that it must involve the rearrangement of "ponderable molecules", not the mysterious passage of a vital force.

Santiago Ramon Y Cajal (1852-1934): Spanish neuroanatomist who refined Golgi's staining technique to produce some of the first detailed drawings of a variety of types of neurons. Disagreed strongly with Golgi, asserting that neurons were separated by synaptic space. Below right are facsimilies of drawings of cortical neurons made by Cajal.

Franz Nissl (1860-1919): Born in Germany, he gravitated to medicine and as a student in Munich he wrote on pathology of cortical cells in which he used a stain he createdwhich opened up a new era in neurocytology and neuropathology. "Nissl Granules brought out by basicaniline stains perpetuate his name." But he also did outstanding work in psychiatry and demonstrated the correlation of nerves and mental disease by relating them to changes in glial cells, blood elements, blood vessels, and brain tissue in general. He worked with Alzheimer on general paresis. In the last 10 years of his life he did studies in which he established connections between the cortex and certain thalamic nuclei. He will be remembered as a great neuropathologist.

Paul Broca (1861): French surgeon who was closely associated with the development of modern physical anthropology in France and whose study of brain lesions contributed significantly to understanding the origins of aphasia, the loss or impairment of the ability to form or articulate words. He founded the anthropology laboratory at the École des Hautes Études, Paris (1858), and the Société d'Anthropologie de Paris (1859). Much of Broca's research concerned the comparative study of the craniums of the races of mankind. He used original techniques and methods to study the form, structure, and topography of the brain and sections of prehistoric craniums. In 1861 he announced his discovery of the seats of articulate speech in the left frontal region of the brain, since known as the convolution of Broca. Thus, he also furnished the first anatomical proof of the localization of brain function.

Korbinian Brodmann (1868-1918): German physician and anatomist who made a detailed study of the human cortex using the then newly developed Nissl stain. Brodmann described 47 areas based on cytoarchitectonic features such as cell type, density and lamination (numbered simply in the order which he studied them). Brodmann's areas are still widely used today.

John Hughlings Jackson (1835-1911): British neurologist whose studies of epilepsy, speech defects, and nervous-system disorders arising from injury to the brain and spinal cord remain among the most useful and highly documented in the field. Jackson was physician to the National Hospital for the Paralyzed and Epileptic, London (1862-1906), and the London Hospital (1859-94). In 1864 he confirmed the discovery of Broca that the speech center of right-handed persons is located in the left cerebral hemisphere, and vice versa, by finding that, in most cases, he was able to associate aphasia (a speech disorder) in right-handed persons with disease of the left cerebral hemisphere. One of the first to state that abnormal mental states may result from structural brain damage, he discovered (1863) epileptic convulsions, now known as Jacksonian epilepsy, that progress through the body in a series of spasms, and he traced them (1875) to lesions of the motor region of the cerebral cortex, or outer layer of the brain. Jackson's epilepsy studies initiated the development of modern methods of clinical localization of brain lesions and the investigation of localized brain functions. His definition (1873) of epilepsy as "a sudden, excessive, and rapid discharge" of brain cells has been confirmed by electroencephalography, a method of recording electric currents generated in the brain.

Gustav Fritsch and Eduard Hitzig (1860): Published a paper called "On the Electrical Excitability of the Cerebrum", in which they reported that electrical stimulation of parts of the cortex elicited movements of the contralateral limbs. Overturned three of Flouren’s central ideas: that the cortex is unexcitable, that it plays no role in producing movement, and that function is not localized. Bartholow (1874) later replicated these electrical stimulation experiments on a human patient.

Carl Wernicke (1874): German neurologist who related nerve diseases to specific areas of the brain. He is best known for his descriptions of the aphasias, disorders interfering with the ability to communicate in speech or writing. Wernicke studied medicine at the University of Breslau and did graduate work at Breslau, Berlin, and Vienna before entering practice in Berlin. In 1885 he joined the faculty at Breslau, where he remained until 1904. In a small book published in 1874, Wernicke tried to relate the various aphasias to impaired psychic processes in different regions of the brain; the book included the first accurate description of a sensory aphasia located in the temporal lobe. Wernicke also demonstrated the dominance of one hemisphere in brain functions in these studies. His Lehrbuch der Gehirnkrankheiten (1881; "Textbook of Brain Disorders") is an attempt to comprehensively account for the cerebral localization of all neurologic disease.

Neuropsychology's False Start: As this cook’s tour hopefully illustrates, by the early 1900's a discipline similar to modern neuropsychology was actually flourishing--the behavior of lab animals with definable cortical lesions was being studied, and the behavioral consequences of human neurological patients was being described by now-famous pioneers of neuropsychology, the likes of Leipmann, Hughlings-Jackson, Dax, Wernicke, Broca and Holmes. For example, Freidrich Goltz (1890) hypothesized that if, as Fritsch & Hitzig claimed, neocortex had definable functions, then removal of the neocortex ought to result in the loss of those functions. In an experiment that anticipated Lashley’s later work, Goltz conducted such experiments on dogs, discovering that decorticate animals were more active than intact dogs, possessed normal or nearly normal sleep-wake cycles, panted when warm and shivered when cold, had normal spinal reflexes, even complex ones, could respond to sensory stimulation, although with elevated thresholds. Meanwhile, Wernicke was formulating his theory that human brains possessed two language zones, connected by a large fiber bundle. He reasoned that if the two area were disconnected, even though the zones themselves were spared, that a particular speech deficit should occur (later in this century shown to be true by Norman Geschwind). Leipmann hypothesized and later demonstrated that certain apraxias (inability to make discrete movements in response to verbal commands) were the result of disconnections between sensory and motor areas. Leipmann further hypothesized that the left hemisphere played a special part in the production of complex movements, noting that left hemisphere lesions frequently produced bilateral apraxia, whereas right hemisphere lesions often had no effect on either limb. It is very interesting that these important 19th century discoveries were lost for over 50 years, until interest was rekindled by 20th century neuroscientists like Geschwind, Penfield, Hebb, Milner, Kimura and Luria.

Reasons for this loss of early progress include: 1) the original articles written in German, whereas English-speaking scientists came to dominate neuroscience after the turn of the century; 2) the intellectual aberration known as radical behaviorism (Watson) came to dominate and stifle the advance of psychological research in neuroscience; and 3) the original data were often over-interpreted by their discoverers, like Wernicke, and the criticisms leveled against such overzealous interpretations dampened enthusiasm for neuropsychology. 4) Physiological and comparative psychology was over-influenced by the negative results of Lashley (1930's), and stuck to pretty much boring brainstem (hypothalamic) stuff like temperature regulation, hunger and thirst. As a consequence, American experimental psychologists veered in the direction of cognitive processes, and have only lately recovered their senses and returned to neural mechanisms.

Renewal: The renewal of interest in neuropsychology began in earnest following WW 2 (partly due to the new crop of brain-damaged war veterans, as well as the crop of frontal lobotomy patients which arose thanks to the misguided psychosurgical efforts of Portuguese neurosurgeon Egaz Moniz). The rich 19th century material was not rediscovered until the late '60s, by neurologists like Geschwind, Teuber and Kimura, who read German. The vast explosion of technology in neuroscience has also aided interest in human neuropsychology. Allied with neurology, neuropsychology (clinical neuropsychology in particular) probably developed at least one bad habit from the medical model: an overemphasis on abnormal function. This focus on abnormal behavior and the brain defects which may account for it make it too easy to lose sight of the more interesting questions regarding NORMAL structure-function relationships. Fortunately, the advent of sophisticated in vivo neuroimaging techniques, like PET and fMRI, as well as the application of sophisticated experimental techniques to normal and brain-damaged populations alike, is rectifying this situation.

Milestones in Neuroscience Research

4000 B.C. to 0 A.D.

ca. 4000 B.C. Euphoriant effect of poppy plant reported in Sumerian records

ca. 2700 B.C. Shen Nung originates acupuncture

ca. 500 B.C. Alcmaion of Crotona dissects sensory nerves

470-399 B.C. Socrates declares epilepsy a disturbance of the brain

460-379 B.C. Hippocrates states that the brain is involved with sensation and is the seat of intelligence

387 B.C. Plato teaches at Athens. Believes brain is seat of mental process

335 B.C. Aristotle writes on sleep; believes heart is seat of mental process

335-280 B.C. Herophilus (the "Father of Anatomy"); believes ventricles are seat of human intelligence.

280 B.C. Erasistratus of Chios notes divisions of the brain

0 A.D. to 1500

177 Galen lecture "On the Brain"

1500 to 1600

1504 Leonardo da Vinci produces wax cast of human ventricles

1536 Nicolo Massa describes the cerebrospinal fluid

1543 Andreas Vesalius publishes "On the Workings of the Human Body"; discusses pineal gland and draws the corpus striatum

1552 Bartolomeo Eustachio completes "Tabulae Anatomicae"

1573 Constanzo Varolio names the "pons"; first to cut brain starting at its base

1583 Felix Platter states that the lens only focuses light

1586 A. Piccolomini distinguishes between cortex and white matter

1587 Giulio Cesare Aranzi describes ventricles and hippocampus

1590 Zacharias Janssen invents the compound microscope

1600 to 1700

1604 Johannes Kepler describes inverted retinal image

1609 J. Casserio publishes first description of mammillary bodies

1649 Rene Descartes describes pineal as control center of body and mind

1662 Rene Descartes' "De homine" published (He died in 1650)

1663 Fancois Sylvius describes the "Sylvian Fissure"

1664 Thomas Willis publishes "Cerebri anatome"

1665 Robert Hooke details his first microscope

1668 l'Abbe Edme Mariotte discovers the blind spot

1673 Joseph DuVerney uses experimental ablation technique in pigeons

1684 Raymond Vieussens publishes "Neurographia Universalis"; uses boiling oil to harden the brain

1695 H. Ridley publishes "The Anatomy of the Brain"

1700 to 1800

1709 Domenico Mistichelli describes pyramidal decussation

1717 Antony van Leeuwenhoek describes nerve fiber in cross section

1740 Emanuel Swedenborg publishes "Oeconomia regni animalis"

1764 D.F.A. Cotugno describes spinal subarachnoid cerebrospinal fluid

1774 Franz Anton Mesmer introduces hypnosis

1776 M.V.G. Malacarne publishes first book solely devoted to the cerebellum

1782 Francesco Gennari publishes work on "lineola albidior" (later known as the stripe of Gennari)

1786 Felix Vicq d'Azyr discovers the locus coeruleus

1791 Luigi Galvani publishes work on electrical stimulation of frog nerves

1800 to 1850

1800 Alessandro Volta invents the wet cell battery

1800 Humphrey Davy discovers nitrous oxide

1803 Friedrich Serturner isolates morphine from opium

1805 Felix Vicq d'Azyr discovers the red nucleus

1808 Franz Joseph Gall publishes work on phrenology

1809 Johann Christian Reil uses alcohol to harden the brain

1809 Luigi Rolando uses galvanic current to stimulate cortex

1811 Julien Jean Legallois discovers respiratory center in medulla

1811 Charles Bell discusses functional differences between dorsal and ventral roots of the spinal cord

1813 Felix Vicq d'Azyr discovers the claustrum

1817 James Parkinson publishes "An Essay of the Shaking Palsy"

1821 Francois Magendie discusses functional differences between dorsal and ventral roots of the spinal cord

1822 Karl Friedrich Burdach names cingulate gyrus; distinguishes lateral and medial geniculate

1823 Marie-Jean-Pierre Flourens states that cerebellum regulates motor activity

1824 John C. Caldwell publishes "Elements of Phrenology"

1824 Marie-Jean-Pierre Flourens details ablation to study behavior

1824 F. Magendie provides first evidence of cerebellum role in equilibration

1825 John P. Harrison first argues against phrenology

1825 Jean-Baptiste Bouillaud presents cases of loss of speech after frontal lesions.

1826 Johannes Muller publishes theory of "specific nerve energies"

1827 F. Magendie discovers foramen of Magendie

1836 Marc Dax handwrites paper on left hemisphere damage effects on speech.

1836 Gabriel Gustav Valentin identifies neuron nucleus and nucleolus

1836 Robert Remak describes myelinated and unmyelinated axons

1837 Jan Purkyne (Purkinje) describes cerebellar cells

1838 Robert Remak suggests that nerve fiber and nerve cell are joined

1839 Theodor Schwann proposes the cell theory

1839 C. Chevalier coins the term "microtome"

1840 Adolph Hannover uses chromic acid to harden nervous tissue

1842 Benedikt Stilling is first to study spinal cord in serial sections

1842 Crawford W. Long uses ether on man

1844 Robert Remak provides first illustration of 6-layered cortex

1846 Carlo Matteucci invents the kymograph

1845 Horace Wells uses nitrous oxide during a tooth extraction

1846 William Morton demonstrates ether anesthesia at Mass. Gen. Hospital

1850 to 1900

1850 Augustus Waller describes appearance of degenerating nerve fibers

1850 Marshall Hall coins term "spinal shock"

1853 William Benjamin Carpenter proposes "sensory ganglion" (thalamus) as seat of consciousness

1855 Bartolomeo Panizza shows the occipital lobe is essential for vision

1859 Charles Darwin publishes The Origin of Species

1861 Paul Broca discusses cortical localization

1864 John Hughlings Jackson writes on loss of speech after brain injury

1865 Otto Friedrich Karl Deiters differentiates dendrites and axons

1866 John Langdon Haydon Down publishes work on congenital "idiots"

1870 Eduard Hitzig and Gustav Fritsch discover cortical motor area of dog using electrical stimulation

1871 Louis-Antoine Ranvier describes nerve fiber constriction

1872 George Huntington describes symptoms of a hereditary chorea

1873 Camillo Golgi publishes first work on the silver nitrate method

1874 Vladimir Alekseyevich Betz publishes work on giant pyramidal cells

1874 Robert Bartholow electrically stimulates human cortical tissue

1874 Carl Wernicke publishes "Der Aphasische Symptomencomplex" on aphasias

1875 Sir David Ferrier describes different parts of monkey motor cortex

1875 Richard Caton is first to record electrical activity from the brain

1876 Franz Christian Boll discovers rhodopsin

1877 Jean-Martin Charcot publishes "Lectures on the Diseases of the Nervous System

1878 W. Bevan Lewis publishes work on giant pyramidal cells of human precentral gyrus

1878 Claude Bernard describes nerve/muscle blocking action of curare

1878 Paul Broca publishes work on the "great limbic lobe"

1878 W.R. Gowers publishes "Unilateral Gunshot Injury to the Spinal Cord

1879 William Crookes invents the cathode ray tube

1879 Wilhelm Wundt sets up lab devoted to study human behavior

1880 Edouard Gelineau introduces the word "narcolepsy"

1881 Hermann Munk reports on visual abnormalities after occiptial lobe ablation in dogs

1884 Karl Koller discovers anesthetic properties of cocaine

1884 Georges Gilles de la Tourette describes several movement disorders

1885 Paul Ehrlich notes that intravenous dye does not stain brain

1885 C. Weigert introduces hematoxylin to stain myelin

1885 L. Edinger describes nucleus that will be known as the Edinger-Westphal nucleus

1886 V. Marchi publishes procedure to stain degenerating myelin

1887 Sergei Korsakoff describes symptoms characteristic in alcoholics

1889 Santiago Ramon y Cajal argues that nerve cells are independent elements

1889 William His coins term "dendrite"

1891 H. Quincke introduces the lumbar puncture

1891 Wilhelm von Waldeyer coins the term "neuron"

1892 Salomen Eberhard Henschen localizes vision to calcarine fissure

1894 Franz Nissl stains neurons with dahlia violet

1895 William His first uses the term "hypothalamus"

1895 Wilhelm Konrad Rontgen invents the X-ray

1896 Max von Frey details "stimulus hairs" to test the somatosensory system

1896 Rudolph Albert von Kolliker coins the term "axon"

1897 Ivan Petrovich Pavlov publishes work on physiology of digestion

1897 Karl Ferdinand Braun invents the oscilloscope

1897 John Jacob Abel isolates adrenaline

1897 Charles Scott Sherrington coins term "synapse"

1897 Ferdinand Blum uses formaldehyde as brain fixative

1898 C.S. Sherrington describes decerebrate rigidity in cat

1898 Edward L. Thorndike describes the "puzzle box"

1898 Bayer Drug Company markets heroin as nonaddicting cough medicine

1899 August Bier uses intraspinal anesthesia with cocaine

1899 Sigmund Freud publishes "The Interpretation of Dreams"

1900 to 1950

1900 C.S. Sherrington states that cerebellum is head ganglion of the proprioceptive system

1903 Ivan Pavlov coins term "conditioned reflex"

1905 Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon have their first intelligence test

1906 Alois Alzheimer describes presenile degeneration

1906 Golgi and Cajal-Nobel Prize-Structure of the Nervous System

1907 Ross Granville Harrison describes tissue culture methods

1908 V. Horsley and R.H. Clarke design stereotaxic instrument

1909 Cushing is first to electrically stimulate human sensory cortex

1909 Korbinian Brodmann describes 52 discrete cortical areas

1910 Emil Kraepelin names "Alzheimer's disease"

1911 Allvar Gullstrand-Nobel Prize-Optics of the eye

1913 Edwin Ellen Goldmann finds blood brain barrier impermeable to large molecules

1913 Edgar Douglas Adrian publishes work on all-or-none principle in nerve

1913 Walter Samuel Hunter devises delayed-response test

1914 Robert Barany-Nobel Prize-Vestibular apparatus

1915 J.G. Dusser De Barenne describes activity of brain after strychnine application

1918 Walter E. Dandy introduces the ventriculography

1919 Cecile Vogt describes over 200 cortical areas

1919 Walter E. Dandy introduces the air encephalography

1919 Gordon Morgan Holmes localizes vision to striate area

1921 Otto Loewi publishes work on "Vagusstoff"

1921 John Augustus Larsen and Leonard Keeler develop the polygraph

1927 Chester William Darrow studies galvanic skin reflex in US

1928 P. Bard suggests the neural mechanism of rage is in the diencephalon

1928 Walter R. Hess reports "affective responses" to hypothalamic stimulation

1929 Hans Berger demonstrates first human electroencephalogram

1929 Karl Lashley defines "equipotentiality" and "mass action"

1927 J. Wagner-Jauregg-Nobel Prize-Malaria to treat dementia paralyses

1930 John Carew Eccles shows central inhibition of flexor reflexes

1932 Max Knoll and Ernst Ruska invent the electron microscope

1932 Jan Friedrich Tonnies develops multichannel ink-writing EEG machine

1932 Edgar Douglas Adrian and Charles S. Sherrington share Nobel Prize for work on the function of neurons

1933 Ralph Waldo Gerard describes first experimental evoked potentials

1935 Frederic Bremer uses cerveau isole preparation to study sleep

1936 Egas Moniz publishes work on the first human frontal lobotomy

1936 Henry Hallett Dale and Otto Loewi share Nobel Prize for work on the chemical transmission between nerves

1937 James Papez publishes work on limbic circuit; develops "visceral theory" of emotion

1937 Heinrich Kluver and Paul Bucy publish work on bilateral temporal lobectomies

1938 Albert Hofmann synthesizes LSD

1939 Carl Pfaffman describes directionally sensitive cat mechanoreceptors

1943 John Raymond Brobeck describes hypothalamic hyperphasia

1944 Joseph Erlanger and Herbert Spencer Gasser share Nobel Prize for work on the functions of single nerve fiber

1946 Kenneth Cole develops the voltage clamp

1949 A.C.A.F. Egas Moniz-Nobel Prize-Leucotomy to treat certain psychoses

1949 Walter Rudolph Hess receives Nobel Prize for work on the "Interbrain"

1949 Horace Winchell Magoun defines the reticular activating system

1950 to present

1950 Karl Lashley publishes "In Search of the Engram"

1950 Eugene Roberts identifies GABA in the brain

1952 A.L. Hodgkin and A.F. Huxley first describe the voltage clamp

1953 Eugene Aserinski and Nathaniel Kleitman describe rapid eye movements (REM) during sleep

1953 H. Kluver and E. Barrera introduce Luxol fast blue MBS stain

1954 James Olds describes rewarding effects of hypothalamic stimulation

1957 W. Penfield and T. Rasmussen devise motor and sensory homunculus

1960 Oleh Hornykiewicz shows that brain dopamine is lower than normal in Parkinson's disease patients

1961 Georg Von Bekesy-Nobel Prize-function of the cochlea

1963 John Carew Eccles, Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Fielding Huxley share Nobel Prize for work on the mechanisms of the neuron cell membrane

1965 Ronald Melzack and Patrick D. Wall publish gate control theory of pain

1967 Ragnar Arthur Granit, Halden Keffer Hartline and George Wald share Nobel Prize for work on the mechanisms of vision

1970 Society for Neuroscience is founded

1970 Julius Axelrod, Bernard Katz and Ulf Svante von Euler share Nobel Prize for work on neurotransmitters

1972 C. Hounsfield develops x-ray computed tomography

1973 Candace Pert and Solomon Snyder demonstrate opioid receptors in brain

1973 Konrad Z. Lorenz, Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch share Nobel Prize for work on ethology

1974 John Hughes and Hans Kosterlitz discover enkephalin

1974 M.E.Phelps, E.J.Hoffman and M.M.Ter Pogossian develop first PET scanner

1976 Choh Hao Li and David Chung publish work on beta-endorphin

1977 Roger Guillemin and Andrew Victor Schally share Nobel Prize for work on peptides in the brain

1981 David Hunter Hubel and Torsten N. Wiesel-Nobel Prize-visual system

1981 Roger Wolcott Sperry awarded Nobel Prize-functions brain hemispheres

Some of the best references for the events that document the history of the neurosciences are:

M.A.B. Brazier. A History of the Electrical Activity of the Brain, London: Pitman, 1961.

M.A.B. Brazier. A History of Neurophysiology in the 19th Century, New York: Raven Press, 1988.

E. Clarke and K. Dewhurst. An Illustrated History of Brain Function, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

E. Clarke and C.D. O'Malley. The Human Brain and Spinal Cord, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968.

S. Finger. Origins of Neuroscience, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

F.C. Rose and W.F. Bynum. Historical Aspects of the Neurosciences. A Festschrift for Macdonald Critchely, New York: Raven Press, 1982.

Copyright © 1997 [Mark

E. McCourt]. All rights reserved.

Revised: September

22, 2001.