Welcome friends and weary travelers. I give you this morsel of psychosurgical madness. More will follow. Meanwhile, please enjoy the original delicacy: Adventures with an Ice Pick: a Brief History of the Lobotomy.

Creative capacity would seem to be an intrinsic function of the frontal lobes. As soon as junior has put one block on top of another and called upon his mother to admire the result he has shown creative capacity. The joy in creation is manifested early in life for there is in all creative endeavor a certain desire to express the self that seeks approbation, and rare is the artist who neglects an opportunity to demonstrate his talent to others.

This factor of creative capacity can best be understood by examining the affective charge responsible. During creative effort the artist concentrates intensely, shutting out distracting sights and sounds, searching around in the field of his experience for something elusive, something intangible, something that others have felt and experienced and portrayed by word of mouth, on canvas, in bricks and mortar, in chemical formulae, in sound waves or in atom bombs.

Creative endeavor is hard work. It is fatiguing to the mind; it is stimulating, exciting, exhausting, yet the exultation of creative effort is something a man learns to appreciate and that he remembers from time to time at later periods with a feeling of satisfaction in performance if it has been good and a feeling of revulsion if it has been bad. In creative endeavor one cannot stress too forcibly the emotional element.

Indications of creative ability are so common among children as to be considered part and parcel of their normal development. Whether this takes the form of a crude drawing labelled "Mama and Daddy" or whether later on, it takes the form of writing novels and verse, or playing a musical instrument, the creative effort must be accompanied by execution in order to bring satisfaction to the individual. When the child sits down at the piano and plays scales under supervision of the teacher, there is so little satisfaction that only dogged persistence of the parents and the teacher will succeed in getting the child to achieve mastery of the instrument. However, let the child pick out "The Happy Farmer" and hear something that makes sense, then it becomes a model for better performance in the future.

Creative effort requires a constantly expanding field of endeavor. As a small boy goes on in his experience in drawing or in wood carving, he progresses from boats to autos to planes to houses and cantilever bridges. As the girl begins to master knitting needles she goes from washrags to doilies, to sweaters, to socks. There is something formal about this type of activity — it has to conform to a certain pattern, it has to achieve a certain perfection, it has to be of a certain value, to be appreciated by the artist and by anybody else except possibly an indulgent mother. All this requires concentration, application, practice, and a certain degree of mastering of the technic, which gives a gratifying sense of achievement.

Creative effort of any advanced degree demands production, and this is apparently where the schizophrenic breaks down. The schizophrenic would rather excel in fantasy than fail in reality, and consequently he develops a tendency toward creation in fantasy without the necessity for the hard work, drill, practice, and humdrum execution of the necessary groundwork. If he can succeed so easily in his endeavors, if what he writes or paints or builds or composes has some special meaning to him which is concealed from others, he achieves a perverted satisfaction from this and also from the knowledge that only he has the mentality to appreciate it. This is obviously a queer way of looking at things and certainly not conducive to the creation of imperishable art. Artistic creation has to meet certain rather exacting standards if it is to be generally appreciated. One can leave aside for purposes of this discussion the esoteric productions which excite such delirious reactions of joy among the cognoscenti. There must be a certain simplicity and directness and a certain appeal to the common sense, a realization of the capacity of the observer to achieve satisfaction in the normality of the artist's production in order that the artist shall enjoy more than ephemeral fame. Just where the border line occurs it is impossible to say, since there are variations among people from one generation to the next. It would be out of place to compare the distortions of certain modern artists with the impressionism of the past century further than to say that if Salvador Dali is crazy he is crazy like a fox, with his limp watches and his spider-legged elephants. In spite of the "stream of consciousness" productions of certain writers of the recent past, Gertrude Stein's statement, "A rose is a rose is a rose" flavors of the schizophrenic, while "Ulysses" becomes an enigma to the critics of a rising generation.

The thing becomes more complicated when musical compositions are brutally criticized as derogatory to the State. One can only ask: "Who's loony now?"

The authors must take refuge in the time-honored saying: "I don't know anything about art, but I know what I like." Schizophrenic art has been studied in some detail by Schilder and by Lewis, and Reitman has recently discussed the "creative spell" of schizophrenics after prefrontal lobotomy: The pictures produced by schizophrenics show certain distortions with a tendency to fill in all the space, with symbolic representations that have special meanings, with obscene details and a general lack of form and color sense. On the other hand, the pictures produced by individuals with serious cerebral trauma show paucity of detail, a certain orderliness and formality but with expansion or contraction of figures and curves instead of angles. Adjoining configurations may be completely separated from one another. In cases of prefrontal lobotomy in schizophrenics there would theoretically be a combination of the two clashing trends, but lobotomized schizophrenics do not seem to fit into either category.

In the days immediately following prefrontal lobotomy, once a patient has lost interest in the doll or the toy dog, we like to give the patient a picture book and a box of crayons. The productions are at first strikingly like those of a small child, with poor color choices and running over the outlines. However, in two or three days, if the patient enjoys this type of activity, he develops a sense of neatness and accuracy with still immature though creditable performance. Not infrequently when a sketching pad and pencil are given to the patient the "creative spell" begins. The drawings are usually quite rigid and formal and may be copied from pictures in a magazine, or they may represent figures that have been drawn in the past, with false emphasis upon shadows, unrealistic proportions, and figures of various sizes filling the space. Object and background relationships are poorly maintained. If an animal is drawn its tail may run off the side of the picture.

Some patients make sketches of nurses and doctors, and we have collected a number of portraits of ourselves that can hardly be termed flattering. Only rarely, as in the case of Case 143, do the art productions become frankly obscene, and in this case it seemed to be rather a carry-over of his obsessive tension state that had been present long before the lobotomy.

Perhaps the best example of what happens to creative capacity of an artist undergoing first a schizophrenic psychosis and then a radical prefrontal lobotomy is shown in Case 68.

Summary. A schoolteacher underwent prefrontal lobotomy during a second attack of schizophrenia. There was considerable inertia followed by restlessness. The family was not helpful and the patient made a poor adjustment, drinking to excess and sinking to the level of chambermaid before finally entering an institution. She remains delusional but without much affect.

Before her psychosis she was artistically inclined, wrote verse and painted in oils. After operation she resumed these arts for a brief period but the performance was of poor quality.

Case 68

The patient was a 36 year old unmarried schoolteacher who first consulted us in 1936 with regard to a lobotomy for her mother who was in an institution because of involutional psychosis. The father was alcoholic and led a hermit-like existence, and the patient herself had studied constantly to make herself a better schoolteacher and had held numerous positions, teaching art and music as well as English in various girls' schools. It was obvious that the situation did not lend itself to surgical treatment of her mother, but it then came out that for three years the patient herself had suffered from violent headaches, had become more irritable and seclusive. She had spent several months in a mental hospital in 1934, following a suicidal attempt and had spent her savings on a trip to the grotto at Lourdes with temporary relief from her distressing paranoid ideas. The plaintive letters from her parents, the lack of success in maintaining friendly relationships with her fellow teachers, and finally an illegitimate pregnancy with spontaneous termination at six months, precipitated a paranoid psychosis which was characterized by rather plausible delusions in regard to her employers, her fellow teachers, her family, her lover, and so on, that disabled her from further effective teaching and made suicide a probability.

Figure 69. Oil painting by an art teacher before onset of psychosis.

During the two and a half years from the first encounter we received innumerable letters, many of them enclosing verses which showed considerable imaginative capacity although some disorganization of her thought processes. In comparison with some of her earlier works along the same lines, they were definitely deteriorated. During the same period, however, she continued with her artistic expression in oil painting and sent us as a present a still-life study of a plant growing in a pot with a very solid shadow that might at first be mistaken for a second plant (Fig. 69). The execution was skillful and the imaginative capacity extraordinary. This apparently represented the culmination of her artistic creativeness. Following this she became more and more depressed, preoccupied, and her letters became vindictive, and expressed ideas of guilt and of suicide as being the only way out following complete failure in her life. She was still maintaining herself as assistant matron in a school for delinquent girls, and she compared herself unfavorably with "the sluts," while at the same time expressing her hostility to those around her.

Prefrontal lobotomy was performed in July of 1940, the incisions going further posteriorly than was planned. There was a great degree of inertia, with vesical and rectal incontinence, smearing of feces, outspoken antagonism to the ward personnel, and later on a bland euphoria.

Convalescence was prolonged and was increased in difficulty because of the lack of help from any member of the family. The patient was lazy, indifferent, outspoken, and yet in the course of six months she managed to secure employment as a waitress and chambermaid. She was not tolerated for very long in any one place because of carelessness and bedwetting, and the convalescence was further complicated by resort to alcohol.

During this period she continued to write numerous letters, childish, ill-expressed, vindictive, expressing more openly the idea that men were trying to seduce her. She still retained considerable energy drive, but it was poorly directed and characterized by restlessness. When intoxicated she would burst forth in angry denunciation. She sank lower in the social scale until she was finally on relief, and arrested a few times for intoxication.

Figure 70. Oil painting by same patient a year after lobotomy.

The creative urge showed itself in a footstool that would have done credit, as far as the design and execution were concerned, to a twelve year-old girl, and also in a still life on canvas, consisting of an ash tray, a pipe, a can of tobacco and a letter that were obviously directed toward the object of her fantasies (Fig. 70). The execution of this painting was extremely crude in contrast to the finickiness of the preoperative painting and could hardly be considered more than a daub.

Not long after this her funds ran out, and because of her inability to adjust herself even during the wartime boom, she had to be committed to a mental hospital, where she still remains. There have been no further drawings or paintings; one or two efforts at verse were immature in concept and shattered in execution, and her letters, once voluminous and vindictive, have now deteriorated into postcards of the "Please send —" variety.

Comment. The effect of operation in this case had been the elimination of the depressive elements in the psychosis without much influence upon the paranoid reaction. Before lobotomy the patient's drive for artistic self-expression in letters, verses and painting was blocked by intense emotional distress. After a brief postoperative surge it descended first from the abstract to the concrete, and then toward the zero mark. It might be argued that the lobotomy was the major factor in the reduction of her creative ability, but without operation she would in all probability have ended up in the back ward of a state hospital or as a suicide. The deteriorating effects of alcoholism and the lack of family interest (her sister committed suicide in an institution) militated heavily against her chances of successful adjustment. She is cheerful, less facetious, not much of a ward problem, and still thinks that every man, including her doctor, is intent on seducing her.

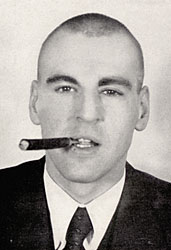

Figure 71. Case 123. March 31, 1942, before operation. Perplexed, unable to solve the simplest problem.

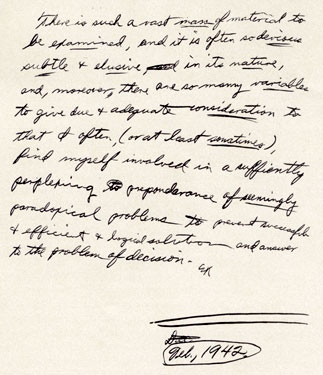

Literary expression drops off in quality and quantity following prefrontal lobotomy. Some of the letters that patients have written to us concerning their experiences with regard to obsessions and compulsions reveal a fascinating subjective approach to problems in human behavior. Case 123, for instance, (Fig. 71) expressed in very graphic terms his perplexity and inability to solve even the simplest problems (Fig. 73).

Figure 72. Case 123. Ten days after operation. He was no longer troubled by his obsessions, and seemed rather pleased with himself.

Figure 73. Case 123. Before lobotomy. "Perplexing preponderance of paradoxical problems."

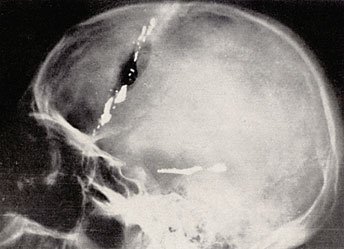

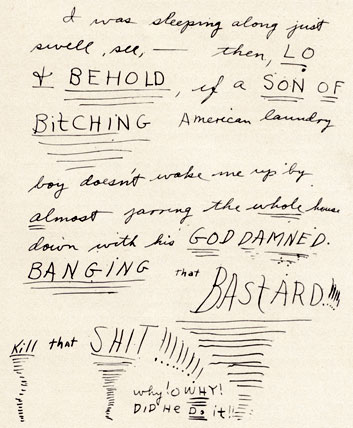

A standard prefrontal lobotomy was performed on April 1, 1942, and Fig. 74 shows the plane of incision. About ten days after operation he was no longer troubled by his obsessions and he seemed rather pleased with himself (Fig. 72). Some months after operation the patient found no difficulty in expressing his sentiments (Fig. 75).

Figure 74. Case 123. Roentgenogram showing plane of incision in standard prefrontal lobotomy, April 1, 1942.

Figure 75. Case 123. Three years after lobotomy found no difficulty in expressing his sentiments.

Case 309 was brought all the way across the country by her mother. The patient had been somewhat of a virtuoso with the violin and had had favorable concert notices at the age of 15. Some of her musical compositions had been published. She developed a schizophrenic psychosis and spent the years from 1933 to 1935 in a mental institution, followed by ten years at home in sullen indifference and sarcastic seclusion with her adoring mother. During these twelve years she never touched her violin. The mother, nonetheless expecting a miracle, brought the violin along in its battered case, and the day after prefrontal lobotomy Violet started playing, probably with about as much expression as she achieved the first day she had touched her instrument (Fig. 76). The operation was a success, however, in that the patient was eventually discharged as recovered in December 1946, and is no longer carried on the rolls of the state hospital. She played the violin with a certain technical excellence during the period of convalescence, but became more interested in listening to the radio and in watching her mother do the housework. When she plays now it is only on the request of her mother, for a short period of time, and the same old pieces that she learned before she became sick. Her execution is fairly adequate, her expression rather rigid and formal, and she has shown no interest in improving herself or in making any return for the sacrifices that her mother made to give her a musical education. In 1949, this woman, now over fifty years of age, had five violin pupils and had herself given several recitals. Credit for these accomplishments must be given the mother.

Almost the same story with a sadder ending, however, was repeated in the case of Case 14, whose sole worldly possession was a magnificent harp which she had played in a large symphony orchestra before her illness. Four years of schizophrenia plus two lobotomies have turned her into a fat, lazy and sarcastic individual. She now plays her harp only on her mother's request or sometimes "to keep my fingers from going soft." There is no indication of progress either in performance or in willingness to practice. The playing is stereotyped, formal and soon terminated.

Figure 76. Case 309. The mother brought along the violin in its battered case. The day after operation Violet played for the first time in twelve years a song "For You Alone" that she had composed twenty years before.

Many of our patients have been able to play the piano. Performance in these cases seems to depend more upon the duration of illness and the deterioration than upon the lobotomy. Patients who have been psychotic for a long time and who have required an extensive incision may show a peculiar forgetfulness of one hand (as in Case 221) so that the treble continues while the left hand rests on a certain chord in the bass. Other patients are quite willing to play for an audience but seldom to amuse themselves. Patients play the piano well. They choose the classical pieces. They pick up the sheet of music that lies on top of the piano and play that. Next time they play the same piece over again. They don't ask for new pieces, and they do not seek new effects in the old ones. A few patients play for their own enjoyment and make progress in technic and expression. Most of them don't seem to have the desire to accomplish something in an artistic manner; they do not experience the emotional exhilaration that comes from brilliant interpretation of a piece of music.

If music is considered in its recreational sense, then it is enjoyed by a large number of patients who have undergone prefrontal lobotomy, but this is apt to be at a low level of discrimination and still lower level of performance. Patients will tune the radio to one particular station and keep it going in spite of more elevated programs coming on other stations. The distracting element in music also enters into the picture. Quite often patients will be distracted from a particular activity they are carrying out at a given time and will walk over and turn off the radio even though other members of the family may be interested in listening to the program.

Reitman reports an interesting observation in the case of a music teacher who had never done any compositions of her own. Within a few days after lobotomy she would play the piano for hours although during the psychosis she was unable even to touch the keys. She also composed five musical pieces:

"Though the main character of her musical work lies in its conventional pattern whereas her drawings were deteriorated so far as their formal elements are concerned, in music she did not deteriorate into 'modernism.' The tempo, however in her first composition is alien. The second composition shows improved key sense and the harmony of the composition is better than that of the first one; it is scholarly and well composed. Thus, she showed a progressive improvement in the formal element; but artistically her work deteriorated in the third, fourth and fifth compositions. As far as the content is concerned, the euphoria and harmonical extraversion are the main characteristics. It is significant that with her rapid recovery and personality readjustment she gave up composition and returned to her original interest: interpreting music, i.e., piano playing."

We have had no experience with professional singers, although there have been a few amateurs. When lobotomy is carried out under local anesthesia, the patient's tension is usually so great that when he is asked to sing "America" only a few croaking sounds issue from the parched throat. As the operation proceeds and the tension subsides, the voice becomes more flexible and patients can sing with considerable fidelity. We recall one patient, Case 443, who started off in very anxious fashion, saying that he couldn't sing a note, and who, once the sweeping incisions had been made in both frontal lobes, could carry the tune and finally when the stab incisions were made, could harmonize with a resounding bass.

Singing or humming in rather monotonous singsong fashion is not uncommon in the convalescent period, and later on some progress may be made in musical expression in this form. However, singing as a means of personality expression, as a means of diversion, and as a means of giving pleasure to others is seldom indulged in. Patients will go to church and sing the hymns in the same old way that they did beforehand, but as far as barbershop quartets or choir singing are concerned, these have lost their zest. Patients retain their capacity for musical expression, but they don't care enough about it to work toward the goal of perfection. In this respect, also, there is sometimes observed a progressive giving-up of this means of artistic expression. When patients find that they can get along without music, which formerly meant so much in their lives, they do so without a qualm.

Case 360 started on her dancing career at the age of 5 and could do toe dancing, tap dancing, acrobatic dancing and others, and had appeared on the stage any number of times as a child in ballet, but Doris didn't stop growing until she was five feet eight and thought herself insufficiently dainty to keep on with that career. At the age of thirteen she became definitely seclusive, with some depersonalization, and her obsessive state failed to respond to a course of electroshock therapy. Following prefrontal lobotomy, and apparently for the first time, she experienced visual hallucinations in which Satan played a prominent part. The experience intrigued her rather than anything else. She was not worried or upset about it, and when the hallucinatory phase passed off she became much better integrated. But aside from a few feeble attempts at dancing engineered by her mother, she has thus far failed to express herself through this medium. Even though it was urged upon her to prevent the development of obesity and to encourage her social activity, she simply no longer feels the need of expressing herself in that way.

One of our early cases, Case 12, started a course in interior decorating about a year after her lobotomy and produced for us an uninspired drawing of a parlor in the Adam style. She failed to secure a position in this type of work and went back to her former clerical occupation, maintaining herself satisfactorily for three years until another catatonic episode occurred that resisted shock therapy, so that a radical prefrontal lobotomy was undertaken in 1941. There has been no indication of any interest on her part in the field of interior decoration in the eight years that have elapsed since the completion of her course.

More practical expressions along the line of interior decorating have been seen in Case 215, a widow, who gave up her old house and moved into a smaller one which she completely redecorated with excellent taste and enjoyed a round of social engagements with particular emphasis on garden parties. Her garden, which she attended assiduously, was extremely well-planned and very decorative. In this case there was no hint of deterioration and the lobotomy was undertaken for the relief of a long-standing hypochondriasis with fixation on the colon.

This is an exceptional case. In most instances patients who are presented with the problem of redecorating, rearrangement of furniture and moving to a new environment, and so on, are content with what they find, or make what readjustments are necessary, and they do not seem to experience the thrill that comes to so many women when faced with the prospects of doing over a house. They are usually willing enough to follow out suggestions but lacking in seeing what ought to be done.

Amateur theatricals are lots of fun for some people imbued with the desire to excel. Case 147 is the only person we know of who has appeared on the stage and then in a bit part in connection with the recreational therapy program engineered by her father. It was not a brilliant success, but the effort was repeated, with considerable success. Kathleen later appeared as leading lady.

Creative capacity in artistic, literary, musical, theatrical and other fields undergoes a decided reduction after prefrontal lobotomy. In the early stages of recovery, there may be some carryover of the original endowments and ambitions just as there is a carryover of the psychotic behavior, but with the progressive reintegration of the personality on a more practical basis the need for expression of the personality along creative lines tends to subside, and the bursts of creative activity that may have been so gratifying to relatives in the immediate postoperative period gives way to rather placid indifference. Adjustments in other respects may be quite satisfactory, but the spiritual, aesthetic and recreational values of the arts seem to have suffered from permanent and even progressive reduction. The inspiration and emotional satisfaction that comes from artistic achievement are no longer experienced, and the patient, satisfied with inferior performance and unwilling to take the time and trouble to achieve a certain degree of excellence, is apt to let time slip by without cultivating the gifts that were so assiduously advanced before the breakdown occurred. While the dexterity and capacity may be unimpaired, it is the emotional driving force that is cut off and, consequently, the capacity dies of inanition.

When one thinks of it, the capacity to imagine a baseball game in which the individual is playing all parts simultaneously is a creative feat of a high order of magnitude (Case 322). Also, the capacity to imagine what would have happened had the early Norsemen intermarried with the Indians and then descended upon the colonists before they had time to become established, indicates at least a vivid imagination (Case 333). And the capacity to understand the meaning of all the poets who have ever written, even the most obscure ones, indicates an intellectual development that surpasses the normal (Case 36). All these feats of creative imagination when carried to extremes become so entrancing that the individual loses sight of the humdrum pattern of getting an education or earning a living, and slips by degrees into the omnipotence of being able to save the world, prevent war, cure humanity of its ills, see God face to face and find out once and for all "whether the Virgin Mary masturbated." Then it is time to do something drastic to prevent total disintegration of the personality. And if creative artistry has to be sacrificed in the process, it is perhaps just as well to have a taxpayer in the lower brackets as the result. Social adjustment is possible with prefrontal lobotomy in a fairly large percentage of psychotic individuals, but prefrontal lobotomy smashes the fantasy life and ruins creative capacity in doing so. Since creative capacity is already slated for ruination by virtue of the psychosis, however, the salvage of the individual as a whole from total deterioration is the aim in prefrontal lobotomy.

Creative capacity, relying so much on imagination and fantasy, is very likely mediated by those portions of the frontal lobe appearing last, and disintegrating first, in the normal course of the individual from youth to old age and located anatomically as far away as possible from the immediate motor centers in the precentral region and the old parts of the frontal cortex in the parolfactory areas at the base. Since these creative activities are essentially abolished no matter how far forward prefrontal lobotomy is undertaken, we would be inclined to place them at the extreme frontal pole. These activities represent the highest in human achievement; they are the most easily upset and the first to disintegrate in the process of involution. When these are lost, even though there is very satisfactory preservation of social relationships, one is justified in speaking of the individual as good solid cake but no icing.

![]()