|

THE INSULIN TREATMENT OF SCHIZOPHRENIAFrom An Introduction to Physical Methods of Treatment in Psychiatry (First Edition) by William Sargant and Eliot Slater (1944, Edinburgh, E & S Livingstone). |

| Not long after insulin came to

be generally used in medicine it was found that in small doses it could be used to improve appetite in cases of anorexia, and that there followed a general improvement in the physical and mental state. The clue was not followed up until Sakel came to use insulin hypoglycaemia to counter the symptoms of withdrawal in the treatment of morphine addiction. He found that he got the best results when a sufficient dosage of insulin was given to produce clinical hypoglycemia, and that this phenomenon, hitherto considered dangerous, was readily controlled by the administration of sugar, when the patients were watched throughout. He was led to try its use in the I treatment of schizophrenia, and the Vienna Clinic, which had seen the first introduction of the malarial treatment of general paralysis, provided him with the patients to experiment on. The idea seemed bizarre, but it was found to work. Once tried its results were, in individual patients, so surprisingly favourable that its use spread widely and quickly. In the international congress of 1938 reports were presented of its trial in most of the civilised countries of the world; nearly all of them were favourable. The disorganisation of the war years has to a great extent interrupted its progress in England but it has gone ahead much faster in America. |

Manfred Sakel |

STATISTICAL RESULTS

Reliable statistics are mostly

in favour of the value of the

treatment. In a series of over 400 patients

treated in Swiss

hospitals before 1937, when the technique was still

new,

59 per cent. of persons treated within the first six months

after

onset reached either a complete or social remission. In

the New York State

hospitals of over a thousand schizo-

phrenics treated with insulin 11.1 per

cent. recovered, 26.5

per cent. made great improvement, and 26 per cent.

some

improvement; the corresponding figures in over a thousand

control

patients were 3.5 per cent., 11.2 per cent. and 7.4 per

cent. A comparable

number of patients treated with cardiazol

convulsion therapy did not do even

as well as the control

patients. Furthermore, the treatment greatly shortens

the

duration of the illness. Earl Bond reports that in the Penn-

sylvania

Hospital 95 per cent, of the patients who were

treated and recovered left the

hospital within a month of

termination of treatment; with few exceptions the

un-

treated patients who made spontaneous remissions required

one to three

years for a similar improvement. Thirty-eight

per cent. of his treated

patients remitted, where there had

been previously only 10 per cent,

remission and 10 per cent

improvements occurring spontaneously.

The results are much more

favourable when treatment is

given early. The New York State hospital figures

show that

only 27 per cent. of the patients treated in the first six

months

of the illness failed to improve, whereas this figure rose to

66

per cent. for those whose illness had lasted five years

Taking a dividing

line of 18 months, Earl Bond finds 67 per

cent, recovery and great

improvement with treatment given

before that time after onset, 30 per cent.

after. The prog

nostically favourable patients selected for admission to

the

Maudsley Hospital showed 34.5 per cent. of social recoveries

when

followed up for three years; 70 per cent, of the patients

selected for

insulin treatment recovered in the same hospital

at a later time. In both

these groups the illness had not

lasted longer than a year.

It is not yet known whether

these recoveries will be maintained;

but the three to one ratio in frequency of

improvement in treated

as compared with untreated schizophrenics

quoted

from the New York State hospitals statistics was still

maintained after two

years, and 60 per cent. of the insulin

treated patients were still living in

the community mostly

in a recovered or improved condition. Relapses occur

both in

patients who have recovered spontaneously and with insulin

It may

be that as the years progress treated and control

groups will tend to

approximate; but even if this proves

to be true one would wish to keep the

potential lunatic sane

as long as possible, and to give him as long a period

as

possible of health and happiness. There is also evidence

that the

relapsed schizophrenic is still susceptible to

treatment especially if each

relapse is treated immediately it

starts.

Provided early cases are

treated, it is then probably true

to say that insulin treatment brings about

a remission quicker

and in a higher proportion of patients than occurs

spon-

taneously or with convulsive therapy. There is also a less

unanimous

impression that the quality of the remission

obtained with insulin is better

than that of the spontaneous

remission; this is likely to be true, if for no

other reason than

that recovery takes place earlier under treatment and there

is

less time for the psychological scarring that is the most

terrible

effect of the disease. There is unanimity that in the

earliest months of the

illness the results are out of all pro-

portion better than later on. In some

patients the illness

comes on so insidiously that even retrospectively none

but

the widest limits can be assigned to the time when it started,

and

these patients it is generally agreed are the most un-

favourable

therapeutically. This may quite possibly be not

because the form of the

illness is more malignant—ordinary

clinical judgment suggests the opposite

conclusion—but

because in all these patients the illness is likely~ to have

lasted

for months or even years before it is even suspected.

Finally, it is clear that there

is an art of treatment, in which

some will be more adept than others, and

that operations

cannot be conducted by rule of thumb. Different

workers

have obtained very different results with the same type

of

material, both in the frequency of remission and of

unpleasant

complications. Earl Bond notes that in a group treated in

the

Pennsylvania Hospital between 1936 and 1938 treatment

was given tentatively

and was in the hands of several different

physicians and all possible risks

were avoided; only 46 per

cent. of remissions was obtained in cases of less

than a year’s

duration. After 1938 a single skilled therapist was

employed,

and the comparable remission rate rose to 79 per cent. This

may

be partly because where there is a specific treatment

available, patients

still in the early stages of the illness are

encouraged to seek treatment;

but at least part of the im-

provement in the recovery rate must be

attributed to the

greater expertness of the treatment and the giving of

really

deep comas when necessary. It is only too easy to carry out

the

treatment in a slipshod or incautious way, or to err on the

side of over-easy

discouragement. The successful therapist

will be gifted with enthusiasm and

caution, he will have a

sympathetic interest in and a detached appreciation

of the

personalities of his patients, he will have the general

medical

training that has accustomed him to the handling of

medical

emergencies, and the refined clinical judgment of the

èx-

perienced psychiatrist, and he will have the facilities to give

the

whole of his energy to the treatment of his patients

without administrative

after-thought. The abilities of the

therapist are not less important than the

method of treat-

ment adopted. On his skill alone the recovery of any

particular

patient may ultimately depend.

THE SELECTION OF

PATIENTS

It is rarely indeed that

facilities will exist for the treatment

by a full course of insulin of all

the schizophrenics coming

under observation, and it is therefore important

not to waste

the treatment on patients not very likely to respond

while

denying it to the favourable case. The first point for

considera-

tion is the length of duration of the illness, and this does

not

mean of overt symptoms. The patient who has only recently

come to show

definite and unmistakable symptoms but has

been known to have been gradually

becoming queerer for

several years is not a favourable case for treatment.

The most

favourable case would be the patient who had been well up

to a

few days or weeks of being seen, and he should be selected

even if there is

some lingering doubt of the true nature of the

illness and probabilities only

speak in favour of schizophrenia.

An atypical onset should not be allowed to

develop gradually

over the course of months into an unmistakable

clinical

picture before treatment is begun. This position is likely

to

arise in atypical manic excitements, in obscure confusional

states, and

even in depressive states with a suggestion of

catatonia, of hallucinations

or other suggestive symptoms. In

any case it must be remembered that

schizophrenic psychoses

greatly outnumber all others in persons under the age

of

thirty. From the much greater success in the early case it

follows that

once treatment is decided on it should be begun

at the earliest possible

moment. If there is a waiting list for

admission, the early schizophrenic

should take precedence of

most other patients, firstly for the reason

already given, and

secondly because in the early stages the clinical picture

is

very fluid and an attempted suicide, an attack of excitement

or

violence may remove the patient from the possibility of

treatment where it

has been arranged to another place where

there may be further delays. As even

a few weeks makes a

difference, this would be a serious matter.

The

rapidity with which treatment can be inaugurated

after the onset of the

illness is by far the most important

factor therapeutically. Next in

importance ranks the quality

of the personality before the illness began. A

frank, open and

socially well-adjusted personality reacts better than

one

which has always been shy, shut off, awkward and autistic.

There are

probably a number of reasons for this. The autistic

personality may not have

always been so, but have become

so as the result of an early and unrecognised

schizophrenic

process, which -has perhaps become chronic, only to show

a

recent florid exacerbation. Further, restoration cannot at

its optimum

be to the same level in the defective as in the

thoroughly normal

personality. This is perhaps the principal

factor that militates against the

successful treatment of

schizophrenia in the intellectually

retarded.

Rapidity of onset is generally held to be a favourable

factor,

which would imply that in two schizophrenics in both of

whom the

illness was of three months' duration, the one in

whom it began in florid

form would have the advantage over

the other in whom it began gradually. This

may be because

in the latter the true point of onset would be set further

back ;

but it may also be because the more acute illness is more

easily

reversible.

The bodily physique has been found to be of

importance,

and the pyknic or athletic habitus is more favourab!e than

the

asthenic and the dysplastic. This is a very general

clinical

impression, and has recently been confirmed by

Freudenberg.

Freudenberg has also found that an abundance of "

process

symptoms," such as hallucinations, thought disorder,

primary

delusions, passivity feelings, etc., are unfavourable. A

history

of a previous attack with a full remission, is on the other

hand,

a favourable sign. It is also our impression that an

atypical

quality in the symptomatology is a sign of good omen.

These

favourable and unfavourable factors seem to act

cumulatively, and very

satisfactory results can be expected

from the patient who shows all of the

first and none of the

second, whereas if the opposite is true treatment is

hardly

worth while. In patients who fall between these two groups

the

results obtained will also be intermediate; there will not

be the same

frequency of complete success as in the most

favourable group, but

considerable improvement, sufficient

for social rehabilitation, will often be

obtained even where a

complete remission appears unattainable. It will be

seen that

the factors that favour a satisfactory response to insulin

are

also those clinically associated with a higher expectation

of

spontaneous remission; but this would be an inadequate

argument in

favour of a laissez-faire attitude. The tragedies of

neglected insulin

treatment in England are to-day a commonplace

to the psychiatrist of

experience; we have as yet

seen no tragedies from premature treatment

skilfully applied.

THE RISKS OF

TREATMENT

The risks of treatment are in

general less than the risks of

waiting for spontaneous remission to occur.

Massed figures

gathered in the United States give a mortality of 90 deaths

in

12,000 patients treated, of which about half were due to

hypoglycaemic

encephalopathy, which is thus seen to be the

most serious risk of treatment;

it is, on the other hand, a:n

avoidable risk and is the rarer the more

skilled the operator.

In this series there were also twelve deaths from heart

failure,

nine from aspiration pneumonia, seven from pneumonia

occurring

otherwise, some of which were probably also avoid-

able. The New York State

hospital figures show that there was

a higher mortality in the untreated than

in the treated

patients. It may be that patients with better physique

were

selected for treatment, and if so that could partly explain

the

result. It is also true that the patient's bodily health

rapidly

deteriorates. under an acute schizophrenic psychosis,

thereby laying him open

to a greater risk of tuberculosis and

intercurrent disease .han where the

process is cut short by

treatment. Twelve patients died of pulmonary

tuberculosis

in the control group, only one in the insulin treated group.

A

mortality of less than one per cent. cannot be considered a

reasonable

bar to treatment in the average patient; and the

risk of death or serious

damage to bodily health can be

neglected in all but the physically ill. Any

advanced degree

of cardiac disease is usually considered a contraindication

to

treatment, as are also Graves’ disease, diabetes, liver and

kidney

diseases causing marked impairment of function.

Treatment can be dangerous,

and is rarely successful, above the

age of forty-five.

Careful

investigations have shown that in patients with a

prolonged series of deep

comas there is sometimes a mild

degree of intellectual impairment the effect

is much smaller

than that also seen in patients of all kinds treated by

con-

vulsion therapy, which is far from great or constant. The

degree of

impairment has been of practical importance in

only a handful of patients

reported in the literature, and is in

any case not comparable with the

disability caused by the

disease itself. Mental impairment is of much greater

im-

portance after long irreversible coma, and a severe Korsakow

picture

can result from this. This improves somewhat as a

rule, but usually leaves a

greater or lesser degree of permanent

impairment. Its occurrence is the

principal reason why the

deliberate production of irreversible comas, which

often have

an immediate curative effect on the schizophrenic process,

has

not been extensively tried as a method of treatment, and

should remain

exclusively in the hands of treatment experts

of long experience. A minor but

still important reason why

treatment as early as possible is so desirable, is

that there is a

lesser necessity for repeated deep comas, with the

attendant

risk of irreversible coma.

THE TECHNIQUE OF

TREATMENT

We are indebted to the

Journai of Mental Science for permission to

include in this chapter the

illustration and some of the details of technique

from an article by Fraser

and Sargent 1940

The

beginner would be well advised, before starting this

treatment, to go for a

week or more if possible to a hospital

where it is done on a fair scale. The

technique cannot .be

learned from books alone, and some practical experience

is

necessary of the dangers that may be met with.

The following technique

here described mostly arises from

experience gained from 1937 onwards at the

Maudsley Hospital

in conjunction with Dr. Russell Fraser, and subsequently

in

an E.M.S. Neurological Unit where early cases could be

admitted and

treated under the conditions obtaining in a

general hospital.

Lack of the

best facilities should not prevent treatment

altogether; and the dangers of

treatment under adverse cir-

cumstances may have to be balanced against the

dangers of

delay. It is quite possible to carry out the insulin

treatment

of schizophrenia in a general ward, with the patient

screened

off during the coma period. Nevertheless where schizophrenics

are

going to be treated in any number a special insulin

treatment unit is very

desirable. Excited patients cannot be

easily handled in general wards, and

even quietly behaved

schizophrenics are likely to become noisy and difficult

during

hypoglycaemia. A fairly large room should be taken, in which

all

the patients it is proposed to treat at one time can be kept

economically

under observation: off this there should be

one or two side-rooms available

for the more restless and

noisy. These rooms will be kept at a warm

temperature, as

patients perspire profusely and often throw off their

bedclothes.

To staff the unit a well-trained team of nurses is

required,

of whom as many as possible should have both a ‘general

and a

psychiatric training. Experience of medical and

surgical emergencies is very

valuable in the management of

this complicated method of treatment. A sister

should be

in charge, and on duty during the treatment period every

day.

Changes in staff from day to day mean that minor

alterations in the behaviour

of individual patients during

sopor and coma may be missed, to the danger of

the

patients: for behaviour varies widely from patient to patient

while

remaining very constant to the individual, and a nurse

who knows the patient

well can detect signs of danger Jhat

would not be at all noticeable to anyone

else. Every effort

should therefore be made to keep the team together, and

avoid

changes of more than one of the personnel at a time or at

less than

well-spaced intervals. The sister is of coutse the

most important of all; and

it will be her responsibility to

assemble and maintain the equipment so that

none is astray

at an emergency.

The patients also should be kept together

through the

greater part of the day. Their food intake at every meal

has

to be carefully supervised, and they themselves must be kept

under

supervision to prevent the occurrence of after-shocks

in the afternoon or

evening. If they go out in the afternoon,

it should be in the company of a

nurse supplied with glucose

to give to any of them who may suddenly develop a

recurrence

of hypoglycemic symptoms.

Apart from the usual ward apparatus

such as intravenous

syringes (1 to 20 c.c.), intravenous needles kept

freshly

sharpened and in perfect state, a variety of small basins,

swabs,

surgical spirit, etc., the following special equipment

is required:

blood-pressure apparatus, air-way, tongue-clips,

mouth gag for use in the

event of a fit (a rubber heel covered

in mackintosh or a dog’s small rubber

bone are serviceable),

an emergency apparatus for giving 5 per cent. carbon

dioxide

in oxygen, ampoules of adrenalin, morphine, hyoscine, 10 per

cent.

calcium chloride, sodium amytal, atropine, coramine,

eucortone, nicotinic

acid, vit. B.1, and luminal (all suitable

for intravenous and intramuscular

use). The means of cutting

down on a vein should also be at hand.

On one

or two small portable trays are placed the means of

nasal interruption. The

nasal tubes selected should be stiff and

of fine bore, and should be

discarded when they get soft from

repeated boiling. On the same trays there

will be lubricating

oil, litmus paper and an aspiration syringe for sucking

out a

test sample of the stomach contents through the nasal tube.

The

container of 600 c.c. of 38 per cent. sugared tea (6.5 oz.

sugar to the pint)

is also on this tray. The tea should be

prepared before treatment starts in

the morning and kept till

needed in bulk in a large jug containing sufficient

for the

needs of all patients. This reservoir of sugared tea must be

kept

warm, for instance in a large thermos jug, and from it

the smaller

receptacles for individual trays can be filled just

before

interruption.

Another special tray or trolley holds the equipment for

an

emergency intravenous interruption—one or two syringes each

containing

20 c.c. of fresh sterile 83 per cent. glucose solution

and a sterilised bowl

from which they may be rapidly refilled.

Sealed bottles of 38 per cent.

glucose should also be at hand,

and only opened before the injection starts.

There should be

ample amounts of 5 per cent. glucose saline ready for

emer-

gency intravenous use, but it need not be specially

heated.

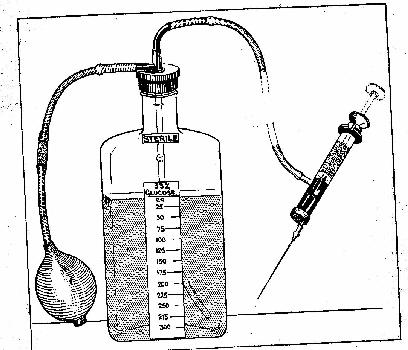

Sarganta and Fraser have adapted

for use in insulin therapy a

composite pressure apparatus which avoids the

necssity of having

to change syringes in giving large quantities of 33 per

cent glucose

or glucose salines intravenously, with the risk of losing one's

place in

the vein every time the change is made. From the illustration it

will

be seen that it is a simple pressure bottle attached to a syringe with

a

side-valve. The needle is inserted into the vein, and with the first part

of the

plunger, blood is sucked into the

syringe, thereby showing that the needle is

in position. Further withdrawal

of the plunger beyond the side-valve allows

the 33 per cent glucose solution

in the pressure bottle to flow freely through

the syringe into the vein.

Bottles of 5 per cent saline are kept in stock which

also fit the same

screwcap of the apparatus. If after the 33 per cent glucose

has been given, a

change to 5 per cent glucose or saline is required, this is

effected simply

by unscrewing one bottle and screwing on the other, pressure

being

re-established by more hand pumping. Through all this, the doctor's

attention

can be concentrated on the more important job of keeping the needle

in place

in the vein, a ticklish matter if the patient is excited and restless,

while

the nurse does the pumping and

changes the bottles if .necessary.

Emergency drugs such as

coramine can be injected into the rubber connection

between

the bottle and the side-valve syringe without further interference

with the veins.

For the avoidance of unnecessary risks, the closest

atten-

tion to record keeping is required. The quality of the records

will

often distinguish a good clinic from a careless one. Four

separate records

are recommended. There should be a tem-

perature chart, on which are

entered the temperature, pulse

and respiration rate daily at 6 a.m. and 9

p.m., the diet taken

(as “full,” “half,” or “excess”), any tube feed that may

have

had to be given, the daily insulin dose, duration of coma and

time

taken to awake after interruption. Any special com-

plication is marked by an

asterisk on the chart. The weight

recorded weekly or hi-weekly is also noted.

A space is left at

the side of the chart for entering the average coma dose

of

insulin and the maximum safe period of coma for that par-

ticular

patient, after these have been ascertained during the

treatment.

A

daily treatment chart is also kept. On it are shown half-

hourly records

of pulse and respiration rate during treatment,

the amount of sweating, the

amounts of insulin and glucose

given each day, the time of onset of sopor and

coma and the

time taken to come round after interruption. Details of

the

patient’s behaviour and neurological abnormalities in sopor

and coma

are also noted here.

In a conspicuous and convenient position in the ward

there

is a treatment board. On it are marked the times of onset

of

sopor and coma, the time when each patient is due to be in-

terrupted,

the time he is actually interrupted and the time

of his awakening. It is

filled in as these events occur by the

doctor and nurses. The important data

it provides can be read

at a glance from any part of the ward, and help to

prevent

delays and omissions when emergencies engage the attention

of the

staff too exclusively to one patient. It is also useful for

providing the

data of the more detailed and permanent records.

Lastly, there should be an

insulin dosage book, in which the

next day’s doses are entered at the end of

each morning’s

work. It is for the information of the sister or nurse in

charge

when giving the insulin the next morning.

Before treatment is begun, it is

desirable to deal with any

septic foci that may be present, at least if of

gross degree and

fairly easily treated. There is evidence that insulin

resistance

is increased by even a mild infective process.

Great importance

should be placed on giving a correctly

balanced diet during treatment. If

possible, measured normal

meals should be prescribed and kept approximately

of the

same content each day. Excess of carbohydrates in the diet

enhances

the probability of after-shocks by increasing insulin

sensitivity. The aim

should be to have every patient on a

constant diet, a regular daily routine

and the same length of

coma each morning. When the metabolism is kept steady

in

this way, it is rare to get sudden changes in the response

to the

morning insulin or the occurrence of after-shock,

Furthermore, any ominous

irregularity in behaviour is

more likely to be noticed and reported. If the

diet taken is

inadequate tube-feeding must be resorted to. It must be

re-

membered that a morning dose of insulin may still be in process

of

absorption for eighteen hours after it has been injected.

Much of the

treatment devolves on the nurse, and on her

skill its success depends.

Provided she is well chosen, the

more responsibility she is given the better

the standard of

work she will attain. The sister and the senior nurses

should

be trained in all details of the technique, from the passing of

the

stomach-tube to the intravenous interruption, and they

should be able to

carry out these procedures with confidence.

They learn to judge for

themselves when the patient is going

too deep, or showing abnormal symptoms,

and to report to the

doctor in time. In an emergency they are taught to act

for

themselves, and may have to do so if complications arise in

several

patients at a time and the doctor’s whole attention

has to be concentrated on

only one. If the selected male and

female nursing staff are trained to a high

pitch of efficiency,

a greater number of patients can be treated than if the

doctor

has to undertake every routine procedure himself. A doctor

must

always be on call, but it is not necessary with a trained

staff for him to be

in the insulin room except during the

times of sopor and coma. If the nurses

have been especially

well selected and trained they can even be left to

handle the

early stages of sopor and light coma provided the doctor

can

get to the treatment ward within a minute of being

summoned.

We give full treatment on five days

a week. On the sixth

half-doses of insulin are given, and the seventh is a

rest day.

If time is short, however, full treatment can be

advantage-

ously given on six days a week. The commencing dose of

insulin

is usually 20 units at 7 a.m. given intramuscularly by

the nurse in charge,

with the patient fasting from 8 p.m. the

night before, and the dose is

increased by this amount each

day of full treatment until sopor occurs, when

progression of

dosage may be slower. When high doses of insulin have

been

reached without sopor, the jump may be 80 to 40 units each

morning

instead of 20 units. Once coma has been induced,

the insulin dose should be

adjusted until the minimum

satisfactory coma dose has been found. Neglect of

this

principle will lead to the occurrence of irreversible comas.

Insulin

sensitivity frequently increases during treatment,

and the regular daily dose

may eventually be stabilised at

half the amount that was necessary to produce

the first coma.

Furthermore, often enough the patient seems consciously

to

resist going into sopor or coma, and when he finally does

so a much

lower dose of insulin is needed to induce the same

state on subsequent

occasions. Sometimes sodium amytal

gr. 3 to 6 has been given by mouth at 7

a.m. when the insulin

is given. This may make the patient less restless and

enable

him to pass more smoothly into sopor. This dose of amytal

is not

enough to make the sleep induced by the drug indis-

tinguishable from the

hypoglycemic phenomena. Sometimes

very high doses of insulin fail to produce

conih at all. Then

the doses must be “swung.” On one day 240 units

should

be given, and then in rotation 40, 120 and 240 units. In this

way

insulin sensitivity may often be increased to the point

where a satisfactory

coma is induced. Insulin resistance up

to 600 units has, however, been

reported, and the phenomena

of insulin resistance are little understood. Some

patients, for

instance, may go into coma with as little as 40 units or

even

less.

There is much confusion about the correct use of the

word

“coma". It is generally agreed that the length of time the

patient is

actually unconscious is the best index of the severity

of a period of

hypoglycemia. Yet in papers on technique

daily “comas” of two and a half hours are

recommended by

some, while others advocate only three-quarters of an

hour.

These discrepancies are due to differences in the meaning given

to

the word coma. The criteria of coma given by Kuppers

have been adopted in our

work. He differentiates the stages

of loss of consciousness into sopor or

pre-coma and true coma.

Because of individual variations it is generally

found that

reflexes, motor phenomena, and most other physical signs

cannot

be used as criteria of onset of either of these stages,

and reliance has to

be placed on tests for the presence or

absence of “ conscious “ or purposive

reactions.

The onset of sopor is usually indicated by the loss of a

normal

response to speech and impairment of orientation.

But testing will still

elicit Ssome confused but purposive re-

sponses. There may be some difficulty

in deciding the exact

time of onset of sopor from earlier degrees of

hypoglyc~mia.

This is not so important as to recognise when sopor

deepens

into coma. The onset of coma is distinguished by the loss of

all

purposive responses, simulating those of the conscious

patient, even on

careful testing. There should be no responses

from visual, auditory or

tactile stimuli. Painful stimuli may

still produce some movements, but these

are not directed

towards the stimulus., Tests should include raising

and

dropping the patient’s arm, trying to make his eyes follow

a moving

object, and giving a painful stimulus such as pressure

on the supraorbital

nerve. As coma supervenes the eyes may

still remain open and some

non-purposive movements persist,

but the absence of purposive response can

always be demon-

strated by testing. Some patients, while still in sopor

and

aware of the test stimuli, lose all initiative to respond. They

must

be distinguished from those in coma, and generally

painful stimuli will

reveal the difference.

THE SECOND

PHASE

The second phase of

treatment starts when the patient

begins to go into sopor. The regulation of

hypoglycaemia to

achieve the maximum degree of safety is best done by

con-

centrating on the duration of actual coma rather than of

sopor. But

very occasionally hypoglycaemia has become

"irreversible” when the patient is

allowed to remain at the

stage of apparent sopor for a very long

tIme. As a precaution,

therefore, interruption is carried out after an hour

and a half

of sopor, if coma has not supervened.

When the patient has begun to

go into coma the length of

the coma period allowed is increased gradually

from five

minutes on the first day to what proves to be the maximum

safe

duration for the individual. Using the criteria given

above, the average

daily period is half an hour, with con-

siderable individual variations above

and below this figure.

The physician should not rely on rule of thumb, but

should

try to discover the safety limit for each patient. He may be

warned

that coma is getting too deep by the patient taking

over twenty minutes to

awake after the nasal feed. He should

be guided by this, or interrupt when

other signs of excessive

depth occur. As the patient’s physique improves with

treat-

ment, longer comas can be tolerated than initially; this will

be

indicated by changes in the depth of coma or alteration in

waking time.

Sometimes it may be desired to take the patient

particularly deep. If this is

done it is wise to interrupt

immediately afterwards by the intravenous route,

and not to

wait a further twenty minutes or less for the patient to

come

round after a nasal interruption—unless after thorough

testing this

has been found to be safe. A particularly severe

coma is also apt to cause an

increased susceptibility to the

next day’s insulin, and this must be

remembered if deep

comas are given. To prevent irreversible coma, a

shorter

coma is advised on the day following a deep coma, particularly

if

there have been signs of shock or delayed awakening. For

the general run of

patients, it is best to give a maximum safe

coma treatment, and to stick to

it each day until recovery is

manifest. Some patients, however, do well with

submaximal

comas, and others need dangerously deep comas to

achieve

results. This is why results vary from therapist to therapist,

and

success depends so much on his skill. With increas-

ing depth of coma comes

an added risk of irreversible

coma, and great skill is needed to handle this

emergency,

but the risk must be faced if it is necessary to the

patient’s

recovery.

Our remarks apply to comas

occurring at the end of the

third and the beginning of the fourth hours, and

are not

applicable to those beginning in the fifth hour. Margins

of

safety must necessarily

be loWer in the latter. The insulin

dosage should be so adjusted as to induce

coma about three

hours after injection.

SIGNS OF DANGER, EXCESSIVE

DEPTH AND EXHAUSTION

Signs of excessive depth call for

interruption at any stage

of coma. The peripheral circulation and blood

pressure are

valuable indicators of circulatory embarrassment, and

re-

peated examination of the finger tips is advisable. When the

blood

pressure falls below 100mm. or the peripheral circulation

becomes poor the

coma should usually be interrupted. A

falling blood pressure and a rising

pulse or respiration rate

should always be regarded as a danger sign,

especially if

combined with signs of failure of peripheral

circulation.

Interruption must be done in good time; the tube feed may

be

vomited or poorly absorbed, and when intravenous inter-

ruption is attempted

the veins may be found to be collapsed

and may then have to be cut down on.

If pulse irregularities

first appear during the later stages of coma and the

pulse drops

below 55, interruption is advisable. Earlier pulse

irregularities

before the onset of coma often subside with its onset,

and

should only require caution when they are frequent or persist

for over

half an hour. As a general rule, provided the blood

pressure remains above

100, the pulse volume is good and the

pulse between 70 and 100 per minute,

these patients may be

left for three-quarters of an hour before interruption.

Some

patients who start with extra-systoles in the initial stages

of

treatment lose them as treatment progresses.

Motor neurological signs

are of little help in determining

the onset of coma, but they are useful

indications of its depth.

In the earlier phase various types of movement may

appear;

they are clinically important only if they are excessive

and

produce exhaustion. Occasionally they may be the pre-

monitory signs

of an impending fit. The movements should

not be allowed to continue for over

an hour and a half or less

if the patient is becoming exhausted by them.

Premedication

with luminal gr. 1 to 2 or sodium amytal gr. 8 to 6 may help

to

diminish them or prevent their occurrence. If the jerking and

movements

are too great it is sometimes advisable to give

intravenous sodium amytal gr.

2 to 3.5 at the time to reduce them.

The drowsiness induced by such a

small dose of intravenous

amytal is easily distinguished from true coma and

may

enable the patient to pass through the restless phase

into

coma.

According to Mayer-Gross severe

hyperkinetic conditions,

restlessness and noisy excitement, can also be

controlled by

giving a part or the whole of the morning insulin dose

intra-

venously. This brings on the deeper and quieter stages of

coma more

quickly. One has to learn by trial in each case

how much of the total dose to

give intramuscularly early on,

and how much intravenously at a later stage in

the day’s

treatment.

In the deeper stages of coma

waves of extensor tonus

occur which are well seen in the arms as combined

extension

and pronation. They are really important, as they indicate

that

the safe limit of coma is being reached. But these move-

ments are often

precipitated or exaggerated by respiratory

embarrassment or circulatory

failure. If the air passages are

freed by inserting a Hewlett’s airway and

the extensor tonus

then subsides, coma may be allowed to continue. When

these

waves of extensor tonus are only spasmodic and the state of

the

circulation is satisfactory, coma may be continued for a

further fifteen

minutes before interruption. But to be on the

safe side it may be advisable

to interrupt intravenously at the

end of this time and not await the slower

operation of a nasal

feed. If the waves persist for longer than a minute, or

the

circulation is poor, immediate interruption should be

done.

Generalised tremor when the patient is not cold is another

important

sign of excessive depth and calls for early inter-

ruption. After going into

coma sometimes the patient

awakens spontaneously, generally after a period of

severe

spasmodic movements. If he is allowed to relapse into coma

agail

after this it should oniy be for half the normal length of

coma, or even

less, as this phenomenon may be the precursor

of an irreversible coma. The

condition of the reflexes is of

little help in giving warning of excessive

depth. More im-

portant is any change from the usual ueurological

pattern

seen during previous comas. If unconsciousness seems deeper

or the

neurological pattern different from the usual for that

particular patient,

and the circulation is poor, interruption

should be done as a precautionary

measure.

OTHER

COMPLICATIONS

Epileptic fits occur early or

late in the hypoglycaemic

period. The early fit occurs 45 to 100 minutes

after the start

of treatment and before the onset of coma. It is

generally

easy to manage. Often after it is over the patient wakes

up

spontaneously and can drink his sugared tea, or glucose can

be given

nasally or intravenously if he remains confused.

Fits occurring in late sopor

or during coma are more dangerous

and may be followed, especially in the case

of those occurring

in the later stages of coma, by delayed recovery or

severe

shock. Immediate intravenous interruption is necessary for

these

later fits. Sometimes absorption of sugar from the

stomach does not occur for

some hours afterwards, and

therefore further intravenous glucose may be

necessary in an

hour’s time, and even again later in the day. Fluids

are

valuable when signs of shock are present; up to 500 cc. of

5 per cent.

glucose saline may be given after an initial 250 cc.

of 33 per cent. glucose

intravenously. Late fits in the stage

of. coma probably indicate excessive

cerebral glycopenia,

and that is why they should be dealt with efficiently

and

rapidly.

Respiratory complications

occasionally arise from aspiration

of saliva during coma, because of increase

of salivation and

diminution of protective reflexes. In the later stages of

sopor

and during coma the patient is best turned on his side to

permit the

saliva to drool out of the mouth. Respiratory

stridor occurring in coma and

not due to blocking of the air

passages nor relieved by passage of an airway

calls for im-

mediate intravenous interruption as it may be a

dangerous

complication.

Vomiting after nasal interruption can often be

dealt with by

giving atropine gr .001 to .02 intramuscularly some

minutes

before the nasal feed. It is only a dangerous complication

when it

indicates a condition of shock. If it does, the treat-

ment of shock will be

required, i.e. intravenous glucose and,

if necessary, saline.

INTERRUPTION

In the lightest stages of

hypoglycemia the patient can, as

a rule, drink 600 c.c. of 33 per cent.

sugared tea (for preference

flavoured with lemon) at the end of

treatment. In sopor and

coma the same amount has to be given by means of a

nasal

tube. When the tube has been passed, gastric juice should

be

withdrawn and tested for acidity with litmus paper before

the sugar is poured

down the tube. When the gastric juice

is only weakly acid a teaspoonful of

salt is added in case

chloride deficiency is being caused by excessive

sweating.

When coma has been deep it is unwise to allow more than

twenty

minutes to elapse in waiting for the patient to come

round before giving

glucose intravenously. This time may

have to be shortened if coma remains

deep or other signs of

danger are present. When a skilful technique in the

pre-

servation of the veins and the use of the pressure bottle has

been

acquired, therapy may be conducted on the basis of a

routine intravenous

interruption. Longer and deeper comas

can then be given with greater safety.

The state of the veins

must be kept under observation and one or two

unharmed

veins should be always kept in reserve for use in emergency;

if

thrombosis has occurred in most of the conveniently placed

veins a return to

nasal interruptions is indicated. In inter-

ruption by the intravenous route

100 c.c. of 83 per cent.

glucose is generally sufficient, but up to 250 c.c.

may be given

with safety. The patient receives further sugar to drink

when

he awakes.

After the patient has come

round he may be given a light

breakfast. Lunch should be given about 1 p.m.,

tea at 4.30, and

another meal in the evening. The commonest time for

after

shocks is about four hours after interruption. If the patient

is not

taking proper meals additional glucose may be given

at this time as a

prophylactic.. But it has already been

pointed out that too great a

carbohydrate preponderance in

the diet is undesirable. Regular balanced

supervised meals

at the right times and a correct morning dose of insulin

are

the best prevention of after-shocks.

IRREVERSIBLE

COMA

This is a dangerous

complication in which unconsciousness

persists despite the giving of adequate

intravenous glucose. In

severe cases there are pronounced vascular shock,

hypertonus,

writhing movements, and the condition resembles one

of

anoxia. The milder cases

may merely show delayed local

recovery, such as monoplegia or aphasia or a

slight confusional

state of short duration. The severe case may involve days

of

unconsciousness, but with skilful handling death should be

avoided. The

pathology of the condition is unknown; but

treatment must be directed towards

facilitating the entry of

glucose into the brain cells, combating the

alkalosis and

anoxia, and restoration of the circulation to its

maximal

efficiency. We have seen great benefit from the giving of

large

amounts of intravenous salines in these cases. When the

patient does

not come round as he should with the intra-

venous administration of 100 c.c.

of 38 per cent, glucose, this

condition must be assumed to be present; and

before the

needle is withdrawn an additional 150 c.c. of 33 per

cent.

glucose should be immediately given. If the patient still has

not

come round, 10 to 80 c.c. of 10 per cent. calcium chloride,

2 to 4 c.c. of

coramine, 20 mgms. of vitamin B. 1, and 500 to

1000 c.c. of 5 per cent,

glucose in saline should be given intra-

venously, starting as soon as

possible. The end of the bed

should be raised, 5 per cent. CO2 in oxygen is

given to the

patient and warmth applied, including hot-water bottles,

as

for shock. After these measures the degree of shock should

be

subsiding, and the rectal temperature will generally rise,

but the patient is

often still very restless. An injection of

morphia and hyoscine is useful for

allaying this.

An hour after the first

injection a second injection of

250 c.c. of 33 per cent. glucose, together

with a further 500 c.c.

of saline, should be given if necessary. If treatment

has been

prompt and efficient, by this time the danger of acute

collapse

is usually past; but the patient may not recover

consciousness

for many hours or even days. Often absorption from

the

stomach starts again very slowly, and further intravenous

glucose has

to be given later in the day, as insulin is still being

absorbed from the

morning Thjection. A stomach-tube

should be passed when first aid measures

have been completed,

and four-hourly nasal feeds of glucose are given. If

these are

not being absorbed they are withdrawn every four hours and

fresh

glucose substituted until stomach absorption restarts.

Each time the previous

feed is found unabsorbed, or has been

vomited, 500 c.c. of 5 per cent,

glucose in saline should be

given intravenously. In very severe cases in

which it does not

appear

probable that the patient will come round tor a long

time a vein should be

cut down on and a continuous glucose

saline drip started. Blood transfusions

may be given alternat-

ing with the saline drip. Eucortone has been

recommended.

Nicotinic acid mgms. 100 four-hourly may also be given

during

the period of unconsciousness by the intravenous

route via the continuous

drip. The patient’s strength must

be maintained by intravenous feeding till

stomach absorption

restarts.

With prompt treatment recovery

from this condition gener-

ally takes place in the first twenty-four hours;

but a period of

unconsciousness lasting six days has been seen, when

the

doctor had failed to institute emergency measures immediately.

After

long periods of unconsciousness very marked impair-

ment of intellectual

functions will be seen, but a surprising

degree of recovery from this will

occur in succeeding weeks

and months. Following short-lived irreversible

comas some

dramatic improvements in schizophrenic symptomatology

have been

recorded. If, with effective measures, the patient

has emerged rapidly from

irreversible coma, the fact that the

complication has occurred does not imply

that treatment

should be abandoned. It may be started again in three

or

four days’ time, but thereafter the comas must be kept much

shorter. On

several occasions we have known treatment,

started again under these

circumstances, to proceed without

further mischance to a successful

conclusion.

CLINICAL CHANGES PRODUCED BY

TREATMENT

In patients who are going to

react well to the treatment it

will generally be found that after the first

few comas, wakening

from coma leads to an hour or two of a considerably

improved

mental state. Sometimes in the early case improvement

occurs

without the coma stage having been reached. The

most prominent change is a

great improvement in rapport and

the affective attitude. For a time the

patient regards the

doctor and the nurses in a much warmer and more

friendly

manner, suspicion is for the moment in abeyance, and there

is

often a considerable degree of insight into the delusions, feel-

ings

of unreality, etc. After this short interval, however, the

patient sinks back

into his old state, and remains in it for the

rest of the day. Patients who are excited,

agitated or panicky

are often much improved in this respect for a longer

period of

time. As the days of treatment succeed one another

the

beneficial change lasts longer, and the state into which the

patient

relapses becomes less hind less severe, until gradually

the improvement is

maximal. In the most fortunate patients

this may occur with astonishing

rapidity, less than a fortnight

of intensive therapy sufficing to bring about

what appears to

be a complete cure.

In order to judge whether the

maximum amount of benefit

has been gained it is necessary to have a very

thorough

knowledge of the patient’s symptoms and clinical state

before

beginning treatment. As improvement takes place delusions

and other

morbid ideas which have hitherto been concealed

may be brought to the light

of day, and give a false im-

pression to the naive that the state is becoming

more acute.

A very careful clinical examination should be repeated

when

the termination of treatment is being considered; and treat-

ment

should not be stopped if there are any signs of activity

of the disease,

unless it is thought hopeless to proceed any’

further. By this it is not

meant that the patient must have

full insight into the symptoms of the past,

but that there

should not still be hallucinations occurring, or feelings

of

influence or passivity, etc.

Furthermore, it is probably

desirable to continue a more

modified form of insulin treatment until the

patient has

regained the physique that is normal and healthy for him.

It

is quite possible that relapse is more likely, even when there

is complete

restoration of mental normality, if a really good

state of bodily health has

not been regained. Mental im-

provement and physical improvement usually go

side by side,

but one may lag a bit behind the other. If the patient

regains

his normal weight and physical state, and retains his

mental

symptoms unaltered, it is a bad sign, and it is usually not

worth

proceeding much further. Most favourable cases respond to

treatment

within two months. Sometimes recovery seems to’

occur two to four weeks after

treatment has been completed.

If no change has been brought about in three

months, and

every therapeutic trick has been tried, it is unlikely that

there

will be a favourable outcome,

USE OF CONVULSIVE THERAPY WITH INSULIN

Although convulsive therapy

is no method of treatment of

the schizophrenic psychosis itself, it can often

play an adjuvant

part, and be particularly useful for dealing with

individual

symptoms. Depression in schizophrenia, as in

basically

different disorders, is often much improved by a few

electrical

fits; and their use before the treatment proper is begun

may

allow the patient to be more easily treated, and may, if neces-

sary,

permit the physician to get a clearer perception of how

much schizophrenic

disturbance there is actually present.

Depression in schizophrenia is

a secondary symptom,

possibly partly psychogenic in origin, possibly partly a

result

of the metabolic changes that are having a total effect on

the

patient’s health; but the intensity of the affective change

may

obscure the realisation of the more fundamental and

ominous symptoms. The

hypothymia, lassitude and anergia,

which are more directly related to the

schizophrenic process

may also clear up under the influence of a few

convulsions,

which are more likely to be required for that purpose after

the

termination of insulin treatment than before it has begun.

Catatonic stupor usually yields

to convulsive therapy, but

sometimes passes into a catatonic

excitement.

Convulsions should then be used if there is doubt of

the

diagnosis, or if the catatonic state interferes with the

practical

details of insulin therapy, e.g. in the intake of an

adequate

diet, Qr if the condition fails to respond fairly rapidly

to

insulin and a depressive component is suspected. The insulin

treatment

will itself be nearly always required to establish

ground gained by

convulsive therapy, and to prevent the

possibility of rapid relapse. Insulin

will also remedy sympl~ms

of thought disorder untouched by convulsions. There

is

some evidence that a few convulsions may be of benefit

during the

course of insulin treatment, for instance when the

patient has started to

improve, but has failed to maintain

improvement. Where the two treatments are

combined they

should be given separately and not on the same day. The

role

of convulsive therapy in schizophrenia is therefore a

supplementary but

important one; the improvements claimed

in the past from convulsions alone

have mostly been symp-

tomatic ones without significance for the course of

the

disease, or have proved temporary. Some of the few apparent

cures may

well have occurred in what were fundamentally

depressive illnesses, with a

schizoid colouring derived from the

structure of the personality. The highest

recovery rate in

any large and varied group of cases .initiaiiy diagnosed

as

schizophrenia will be achieved when insulin and convulsion

therapy are

skilfully combined in differing proportions in

each case, based on the actual

symptomatology shown.

PSYCHOTHERAPY

In our view the time has passed

when one can legitimately

treat schizophrenia by non-physical methods alone,

and the

claims that are from time to time made of the necessity

of

combining psychotherapy with insulin treatment seem to

be exaggerated.

Many patients make an uninterrupted

recovery under insulin treatment without

any special psycho-

therapeutic handling whatever. The apparent

psychological

precipitants of a schizophrenic illness are frequently

found

when the insight gained into the illness is fairly complete to

have

been not part causes of the illness but the earliest signs

of its onset. The

type of psychotherapy that is most required

with the schizophrenic patient is

of a kind that might be found

valuable after any grave physical illness. Once

he is re-

covered the patient has to return to the outside world and

try

to manage his own affairs without the constant advice of the

doctor;

it will often help if the way is made a little smoother

for him. While the

disease is in active progress it is hopeless

to try to influence the

patient’s ways of thinking; but it is not

so hopeless when the fundamental

thought disorder has been

abolished, and there are only a few fragmentary

delusional

beliefs, suspicions or foci of apprehension which are left

over

as relics from the past.

It is probably beneficial to

get into contact with the patient

during the best half hour or so of the day

immediately on

wakening after treatment, and to give him then the

im-

pression of friendly assistance, even though, as is probable,

any

influence one can exert on his morbid ideas is of the most

trifling duration.

As soon as he is well enough he should

be kept fully occupied in the

afternoon with occupation

therapy, gardening, games, walks, visits to the

cinema, and

so on. When

recovery has occurred the possibilities of

explanation and reassurance are

much more favourable.

The patient will probably have a very clear memory for

a

time of his many morbid experiences, and will be anxious to

get some

explanation for them. Reassurance will also often

be required on the subject

of relapse. It should not be

concealed from the patient that relapse may

occur, but he

should be told that the prospects of treatment need be

no

worse, should a relapse occur, than they have been with his

first

illness, and that if he only seeks advice in the early days

of such a

recurrence, they are bright indeed; he should, of

course, on the other hand,

be encouraged not to worry about

himself, nor to keep forever a finger on the

pulse of his mind.

FOLLOW-UP

When recovery has occurred it

is advisable to discharge

the patient from hospital as rapidly as possible.

Return to

the normal environment, and an abbreviated recollection of

the

hospital atmosphere will aid the patient in the recovery of

his

self-confidence and powers of adaptation. But it is ad-

visable to keep an

eye on the patient in an out-patient clinic

fairly regularly for a month or

so, and then it is wise to ask for

three-monthly attendances for another

year. If there is the

slightest sign of any relapse it should be promptly

dealt with,

and though a relapse may occur at any time up to many

years

later, it is most likely to occur fairly soon.

All pages copyright ©Priory Lodge Education Ltd 1994-2003.